My mother, me, and brother

In the summer of 1979, our family set out from our home in Iowa City, Iowa, for Seattle. My father, a professor, had accepted a position at the University of Washington, and we were leaving the Midwest for good.

The university paid for the big moving van, but we had some things to bring along that my parents wouldn’t trust to anyone, chief among them, my father’s wine cellar, which had been growing for many years. The thought of entrusting those 250 or so bottles to a moving van that was not air conditioned as it traveled across the West at the height of summer was not something my father was willing to do.

We were a two-car family. We had a 1965 Chevrolet Malibu station wagon and a 1969 Buick Electra 225. The Chevy had rusted through in some parts around the fenders, and at the back bumper. My parents had gone to Earl Scheib the summer before, and had come back with a paint job that merely sealed the rust in place and barely approximated the original paint. It was now more of a sea-foam green than the gun-metal blue of the original. There were bare spots where the painters had hastily covered up the logos, and the top coat felt scratchy, like a cat’s tongue. The Buick was still in good shape, though years of Iowa winters were also taking their toll on it, and rust was just beginning to bloom around the rear wheel wells.

We were a two-car family. We had a 1965 Chevrolet Malibu station wagon and a 1969 Buick Electra 225. The Chevy had rusted through in some parts around the fenders, and at the back bumper. My parents had gone to Earl Scheib the summer before, and had come back with a paint job that merely sealed the rust in place and barely approximated the original paint. It was now more of a sea-foam green than the gun-metal blue of the original. There were bare spots where the painters had hastily covered up the logos, and the top coat felt scratchy, like a cat’s tongue. The Buick was still in good shape, though years of Iowa winters were also taking their toll on it, and rust was just beginning to bloom around the rear wheel wells.

It was decided that my father and the wine should ride in the Buick, because it had air conditioning. My mother would drive the Chevy, with my brother, me, and the cat. My brother John, thirteen, and I, fifteen years old, were tasked with loading the wine into the Buick.

The Buick Electra 225 was an impressive piece of machinery, more heavy gun boat than car. To sit in its driver’s seat was to be pilot of a massive vessel, the steering wheel more like a tiller or ship’s wheel. The helm answered sluggishly.

The floor of the back seat held four boxes of wine across, with one stacked on top of each, behind the front seats. The rear seats—more a divan, really—held six more, while still leaving room for the driver to see out the back. The trunk kept six more, a total of twenty boxes—240 bottles. When fully loaded, the Buick sat low on its springs, like a bootlegger’s car bound for Thunder Road.

Contemplating the run across country, my father lived in mortal fear of being caught transporting that much alcohol across state lines. He had vivid daylight nightmares where he tried to explain to a Montana State Trooper that these 20 cases were strictly personal use. He was pretty sure it would be not a winning strategy to point out to said Trooper that 240 bottles consumed at the rate of one bottle per night with dinner was not even a year’s supply. After loading it up the night before the move, John and I threw a blanket across the boxes in the back. I’m pretty sure I heard my father get up at least once in the night to stand at the window overlooking the driveway so he could check on the car.

We set out from Iowa City on a warm, clear June morning. We headed slowly out of town, past John’s and my school, past downtown, past City Park and then joined the stream of cars on I-80, heading west.

Our cat, Wayne, was a seal-point Siamese. He was normally sixteen pounds of yowling, marauding menace, but car rides reduced him to mute terror. On the veterinarian’s advice, we’d slipped him a sedative. We put a tension bar across the two side windows of the “very back” of the station wagon and attached his leash to it, so he could move about, which we had hoped would help him cope.

John, Wayne & me

What became clear, even before we had passed Coralville, was that far from sedating him, the drugs had only served to make Wayne feel trapped, like someone in a dream from which they can’t quite wake up, the “witch’s ride,” where you feel paralyzed to move and unable to end the dream, hovering in some trance. The poor cat was a drug-induced prisoner in his own body—and deathly afraid. His eyes were glaucous, mucus-filmed and his nose drained like someone with a bad cold. Barely ten minutes into the trip, he had succeeded in pulling the tension bar out. I reached back, unhooked him from his leash and put him in my lap. He struggled out of my grasp and onto the floor where he crawled under the front passenger seat, where he stayed for the duration of the trip.

Which was long—four days and three nights across the vastness of the West. It was made longer because my father refused to drive even one mile over the speed limit, once again hoping to elude suspicion. John and I argued, my mother tried to make us feel we were embarking on a great adventure, and the cat cowered under the front passenger seat. Seven hours later, we stopped for our first overnight in Mitchell, South Dakota.

I went into the lobby after my father, because I wanted out of the car. He was standing at the front desk.

“Do you have a ground floor room?” he asked. “Something out of the way?”

They had indeed, and we drove to the back of the motel, where the asphalt parking lot opened out onto the vastness of South Dakota scrubland. My father backed the car into the parking space right in front of the door. Dad went in and cranked up the air conditioning as my brother and I unloaded the Buick and brought the boxes into the motel room, stacking them neatly, under my father’s direction, against the near inside wall. A quick trip to McDonald’s across the parking lot, and John and I went to the tiny motel pool. My mother and father sat vigil in the motel room with the curtains drawn.

In the morning, John and I began loading the car. It was barely 7am, but already the heat was rising, and the dun colored landscape seemed to buzz with latent malice. My father had taken the extra precaution of starting the car and running the air conditioner as we loaded. “Keep the doors closed in between loads,” he advised from the bathroom as he shaved. We put a blanket on top of the boxes, and we set out, a mini wagon train crossing the prairie.

As the elder brother, I regarded being able to sit in the front passenger seat as my prerogative, and my mother allowed me, if only to keep me and my brother apart. Where the first day had failed to instil any sense of a grand adventure—we’d been over much of this ground before on a trip to Colorado two years before—the second day at least held a kind of rhythm and sense of progression. Cornfields slowly gave way to dry pastureland, which gave way to the badlands and dizzying heat.

As the elder brother, I regarded being able to sit in the front passenger seat as my prerogative, and my mother allowed me, if only to keep me and my brother apart. Where the first day had failed to instil any sense of a grand adventure—we’d been over much of this ground before on a trip to Colorado two years before—the second day at least held a kind of rhythm and sense of progression. Cornfields slowly gave way to dry pastureland, which gave way to the badlands and dizzying heat.

Even with all the windows down (there was no danger of the cat ever coming out from under the seat), traveling at exactly 55 mph, the heat was scorching, the car seeming to roast us as we stuck, slipped and melted into the vinyl seats. John and I did discover a trick to cool off—even for a moment: all it took was to lean forward in your seat, grab a bit of sweat-soaked shirt and tug it away from your back. Leaning back again, the shirt would give a pleasant chill. He and I worked it out that waiting eight to ten minutes provided optimal chilling effect.

As the sun pounded the car, and I counted the minutes till the next time I could cool down, I would stare at the back of the Electra 225 directly ahead of us and wonder how much nicer it must be in there, sitting on cloth seats. Its Goddamned windows were rolled up! There was an FM radio too.

As the sun pounded the car, and I counted the minutes till the next time I could cool down, I would stare at the back of the Electra 225 directly ahead of us and wonder how much nicer it must be in there, sitting on cloth seats. Its Goddamned windows were rolled up! There was an FM radio too.

The jolt of cool, ozone-scented air the Buick exhaled each evening when we’d unload it was the closest we came to knowing those first few days. Strangely, John and I never quite resented the wine or the arrangement. It was more an obligated nuisance, like making allowances for a grandparent—of course grandma gets the comfy chair in the air-conditioned living room where we can’t watch afternoon cartoons on the TV.

The third night, on our way to Missoula, the Chevy died less than ten miles away from the Little Bighorn battle site. We sat by the roadside with it while my father drove to Billings, an hour away, to rent a car. He came back with an Oldsmobile 98. Since the Olds had a much newer, better air-conditioning system, John and I dutifully loaded it with the wine from the Buick.

The fourth night, we were in Seattle, at our new house in the Montlake District, just south of the University of Washington campus. John and I unloaded both cars this time before we were allowed to explore the new house, which, it turned out, already had a space for a wine cellar.

Beginning the next year, with my 16th birthday, we would drink a Chateau Latour, Margeaux or Lafite from the year of my birth, 1964; and beginning with John’s 16th birthday, we’d drink a ’66 from one of those chateaux. I was glad my parents had had the foresight to take care of the wine, glad to have played a part in it, and glad to share in it.

Beginning the next year, with my 16th birthday, we would drink a Chateau Latour, Margeaux or Lafite from the year of my birth, 1964; and beginning with John’s 16th birthday, we’d drink a ’66 from one of those chateaux. I was glad my parents had had the foresight to take care of the wine, glad to have played a part in it, and glad to share in it.

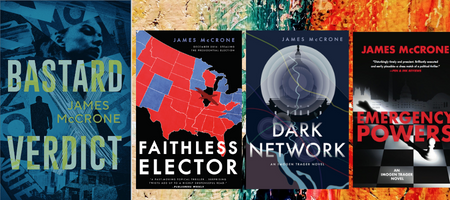

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series Faithless Elector and Dark Network. The third and final book in the series, Emergency Powers, is coming soon.

Find them through Indybound.org. They are also available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Powell’s Books.

Link to REVIEWS

Did you remember to get Wayne out from under the seat? (After the wine was unloaded, of course.)

LikeLike

Yes, indeed 🙂 He lived a long, fruitful and LOUD life in Seattle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Northwest Return | Chosen Words - James McCrone