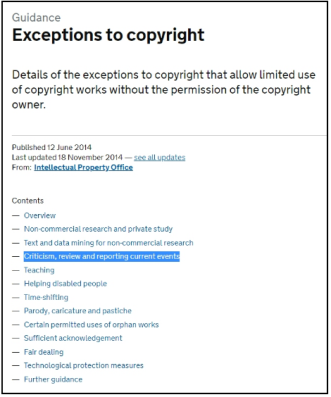

On his blog, Wings Over Scotland, The Rev. Stuart Campbell writes about a Kafkaesque removal of Youtube content by the BBC on its site, ostensibly for “copyright infringement” despite the fact that [from Wings’s post]: “Our videos are all in full compliance with fair-use laws. You are absolutely allowed to record and reproduce clips for news-reporting and discussion purposes. The BBC, of course, knows that perfectly well.”

On his blog, Wings Over Scotland, The Rev. Stuart Campbell writes about a Kafkaesque removal of Youtube content by the BBC on its site, ostensibly for “copyright infringement” despite the fact that [from Wings’s post]: “Our videos are all in full compliance with fair-use laws. You are absolutely allowed to record and reproduce clips for news-reporting and discussion purposes. The BBC, of course, knows that perfectly well.”

Campbell goes on to note in detail that Scottish Conservative party and anti-Scottish Independence news organizations seem not to have run afoul of the BBC’s gatekeepers.

Campbell goes on to note in detail that Scottish Conservative party and anti-Scottish Independence news organizations seem not to have run afoul of the BBC’s gatekeepers.

He details the Byzantine process of closed loops and dead ends he encountered when he tried to appeal. The combination of automated responses and references to appeals processes that lead back to step one is brilliantly—chillingly—effective.

It’s a recipe for Memory Hole 2.0, with a dash of Kafka for spice, leavened with liberal slogs of post-modernist self-reference. Worse, the automated and seemingly reasonable claim of infringement makes BBC’s actions seem like not what they are—silencing the record of dissent.

While this is particularly disturbing for pro-Independence voices, it also points up a larger contemporary epistemological problem: how do we know what we know, if the evidence and facts that underpin our opinions and action are so easily disappeared? How do we hold officials and others accountable when the record of their very words is so slippery?

While this is particularly disturbing for pro-Independence voices, it also points up a larger contemporary epistemological problem: how do we know what we know, if the evidence and facts that underpin our opinions and action are so easily disappeared? How do we hold officials and others accountable when the record of their very words is so slippery?

A friend in the Academy told me recently about a periodical he relies on for his writing and research. To save money and space the university where he works now subscribes only to the online version of the journal and its searchable back numbers. But if the university fails to pay its subscription fee (which happened) or encounters some other difficulty, access to the whole journal, including its back numbers—its history—is lost. In days past, when libraries were late with a payment, the latest issue or volume might be delayed in arriving, but the earlier, already-paid-for editions remained in the stacks. And if the journal were to go out of business, the volumes (the record) would also remain intact. Not so now. What, and how many, such things do we rely on that could vanish?

The so-called “cloud” is rife for this kind of Memory Hole mischief, whether calculated or merely irresponsible. How do you restore what’s lost? To whom do you appeal? In an online space where we the people are constantly expected to certify that we’re “not a robot,” it’s algorithmic ‘bots who are the guardians, and while marvels of technical prowess, they are also unaccountable, aloof engines of plausible deniability.

I’m aware of the irony of writing this on a platform that is itself ethereal, disposable.

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series Faithless Elector and Dark Network.

Find them through Indybound.org. They are also available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Powell’s Books. Link to REVIEWS

The final book in the series, Who Governs, is due out next year.

For a list of appearances and links to reviews, check out:

http://jamesmccrone.com/about.html

There are also a couple of Youtube clips of readings on the about author page.

(Check ’em out, while they last! 🙂

Manchette cites many of my favorites, like John Le Carre and Ross Thomas as having been very influential in his embrace of a new aesthetic. As Ethan Anderson put it in his ‘

Manchette cites many of my favorites, like John Le Carre and Ross Thomas as having been very influential in his embrace of a new aesthetic. As Ethan Anderson put it in his ‘

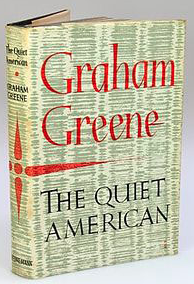

To Manchette’s list of influential writers in this hybrid genre, I would add Graham Greene. His “entertainments,” like The Quiet American, The Third Man, Our Man in Havana and The Honorary Consul are extraordinary. Political events are not just backdrops for Greene’s and the others’ stories, they are integral, giving deeper meaning to the characters’ struggles and to the stakes if they fail. They inform the stories and give them an edge, whether it be Viet Nam as the Americans replace the French (Quiet American), or the gullible Agency in Our Man in Havana. As I struggle to write engaging thrillers, I keep these and other works in my mind, not to copy, but as strong examples of all that’s possible.

To Manchette’s list of influential writers in this hybrid genre, I would add Graham Greene. His “entertainments,” like The Quiet American, The Third Man, Our Man in Havana and The Honorary Consul are extraordinary. Political events are not just backdrops for Greene’s and the others’ stories, they are integral, giving deeper meaning to the characters’ struggles and to the stakes if they fail. They inform the stories and give them an edge, whether it be Viet Nam as the Americans replace the French (Quiet American), or the gullible Agency in Our Man in Havana. As I struggle to write engaging thrillers, I keep these and other works in my mind, not to copy, but as strong examples of all that’s possible.

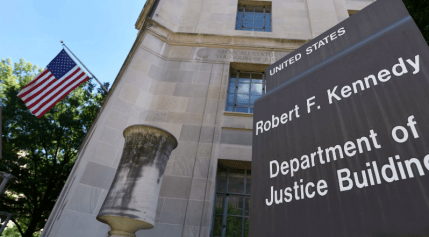

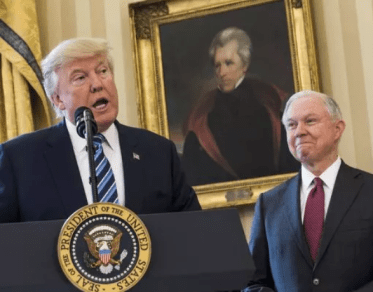

In the real world, we’re shocked to be now confronted with authoritarian propaganda at the highest levels, dismayed by craven apologia for that propaganda; by an increasingly irrelevant, neutered main stream media, and an administration that has its hands on all the levers of power. But this state of affairs has been apparent to anyone with imagination. It’s disturbing just how much these first two Imogen Trager novels get right regarding the context and background in which the conspirators operate—a pliant media, cowed by power, machinations at the highest levels of the Justice Department; fake news, false claims of voter fraud, collusion and corruption.

In the real world, we’re shocked to be now confronted with authoritarian propaganda at the highest levels, dismayed by craven apologia for that propaganda; by an increasingly irrelevant, neutered main stream media, and an administration that has its hands on all the levers of power. But this state of affairs has been apparent to anyone with imagination. It’s disturbing just how much these first two Imogen Trager novels get right regarding the context and background in which the conspirators operate—a pliant media, cowed by power, machinations at the highest levels of the Justice Department; fake news, false claims of voter fraud, collusion and corruption.

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series  In the name of verisimilitude (and telling a good story), I’ve been struggling to get right the atmospherics of our time; to isolate and describe the tactics and threat posed by reactionaries. I wonder at how close I seem to be coming. In that same post, I noted the novels are “about Power,” and that where there is no law, there’s only power.

In the name of verisimilitude (and telling a good story), I’ve been struggling to get right the atmospherics of our time; to isolate and describe the tactics and threat posed by reactionaries. I wonder at how close I seem to be coming. In that same post, I noted the novels are “about Power,” and that where there is no law, there’s only power. James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series