Despite our familiarity with the Electoral College, it bears repeating that the citizens of the United States do not vote for the president but rather for Electors, chosen by the various political parties state-by-state, who promise, that is “pledge,” to vote for their candidate. “There are so many curving byways and nooks and crannies in the Electoral College that there are opportunities for a lot of strategic mischief,” Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) noted in a 2022 interview.

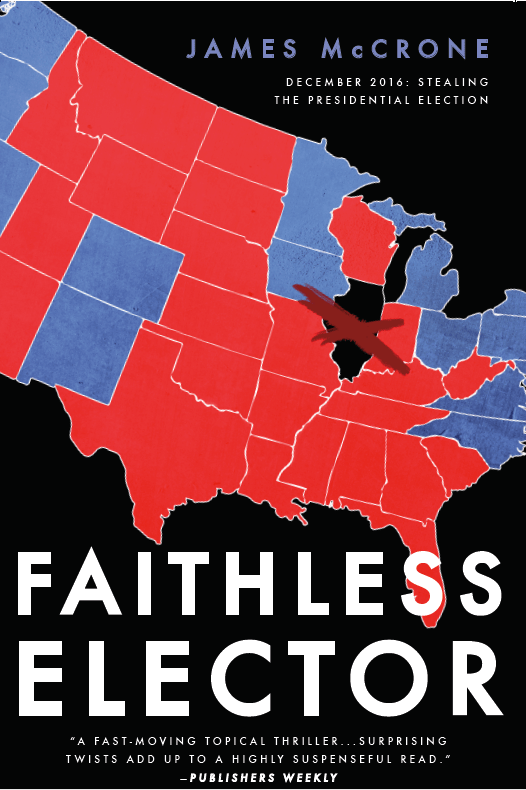

If you follow this blog, you know that my first novel was a thriller called Faithless Elector, in which a shadowy group seeks to steal the presidency by manipulating the Electoral College. My novel is a work a fiction, and I didn’t get everything right. But it’s dismaying to watch so much of its plot play out in the real world.

Faithless Elector debuted in March of 2016, well before the party conventions had selected their respective candidates, so it’s not about Clinton and Trump, but is animated by the question, “What if?” What if a shadow group wanted to steal the presidency by manipulating the Electoral College? The book’s staying power lies in the fact that it’s about a real, latent weakness in the process, prone, as Rep. Raskin points out, to “a lot of strategic mischief.”

And it’s about writers’ questions: Who are the bad guys? What do they want? What are the stakes? How would they go about it? Because first and foremost, for a good story, the protagonist(s) need a strong antagonist. If your “bad guys” are dummies, or the stakes don’t seem compelling, it doesn’t make for much of a story. As a reader, you want to feel the importance of the stakes and the very real possibility that the protagonist might not succeed.

The story is driven by move and counter-move. Verisimilitude (“like truth”) has been my guide, and I had to construct a plausible, mischievous threat. So, to begin with, I looked at the story not as the hero’s journey, but as the conspirators’ plot. I looked at how they might plausibly pervert rules and institutions, what groundwork they would have to create. I zeroed in on the weakest link, the actual Electors, and I made the conspirators resilient, having built into their model an ability to take advantage of serendipitous (for them) unforeseen events.

In the novel, the assumed EC vote tally is separated by only four votes. If three Electors could be persuaded to switch their votes, then the presumed loser would win. When I wrote the book, only a few states had anti-Faithless Elector laws on the books, and no one knew whether those statutes would stand if brought before the Supreme Court (there is much scholarship suggesting that Electors were intended to be decision makers, and despite their pledge were free to vote as they saw fit; but of course, no switched vote had ever changed the assumed outcome). Since the ’16 election a number of states and the District of Columbia (38 in total now) have instituted some sort of anti-Faithless Elector law, leaving twelve states without any such laws, and of the 38, fully half have no enforcement mechanism for their laws.

In the novel, an idealistic young graduate student, Matthew Yamashita, happens to be polling Electors for his dissertation research when he finds a suspicious number of deaths among them–all of them occurring between the general election and the real presidential election, when the Electors meet in their respective state capitols. This year it will be December 17, 2024. Matthew must get the information out to someone who will believe him–and who can do something to stop it. Later, Matthew and his allies realize that though they’ve got most of the facts right, they’ve missed a key point, which has cost them time.

In the novel, the conspirators need to give the Faithless Electors cover for switching their pledged vote, so they set about creating what looks like voter fraud in Illinois. It is the key to their strategy because it sows doubt and causes confusion. Meanwhile, in the real world, the Trump campaign covers all bets–it sows doubt about the validity of voting, and their operatives work to disenfranchise as many voters as possible. We have even seen ballot collection boxes set on fire in and around the Portland, OR, area, putting hundreds of ballots in jeopardy.

Not only is the Electoral College an archaic remnant that has never operated as designed, but since the first fully contested election (after Washington declined to run a third term), the rise of political parties has caused it to grow worse and more convoluted. Worst, far from giving a voice to small state voters, it disenfranchises rural and city dwellers alike. Adding the malapportioned Senate numbers (two per state regardless of population), further distorts the will of the people. The candidates, as has been true for some time now, focus on “swing states,” like my home state of Pennsylvania.

Meanwhile, there have now been five (5) presidential elections where the loser of the popular vote nevertheless became president – 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016. Will it happen again in ’24? Will it be worse?

# # #

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thrillers Faithless Elector, Dark Network , and Emergency Powers–noir tales about a stolen presidency, a conspiracy, and a nation on edge. Bastard Verdict, his fourth novel, is about a conspiracy surrounding a second Scottish Independence referendum. His novel-in-progress is called Witness Tree, a (pinot) noir tale of murder and corruption set in Oregon’s wine country.

All books are available on BookShop.org, IndyBound.org, Barnes & Noble, your local bookshop, and Amazon. eBooks are available in multiple formats including Apple, Kobo, Nook and Kindle.

James is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Int’l Assoc. of Crime Writers, and he’s the current president of the Delaware Valley chapter of Sisters in Crime. He lives in Philadelphia. James has an MFA from the University of Washington in Seattle.

For a full list of appearances and readings, make sure to check out his Events/About page. And follow this blog!

You can also keep up with James and his work on social media:

Mastodon: @JMcCrone

Bluesky: @jmccrone.bsky.social

Facebook: James McCrone author (@FaithlessElector)

and Instagram/Threads “@james.mccrone”