Reality threatens to outpace imagination, and I worry that justice and guilt are becoming quaint notions

Michael Smerconish writes today in the Philadelphia Inquirer about the silence (and poor sales) that come from writing ahead of the curve of opinion and understanding. (I feel your pain, Michael!)

His novel, TALK is about the rise of a right-wing radio host who has qualms about how he makes a living and what his actions are doing to the body politic. When Smerconish published the book in 2014, he says, it was called “far-fetched,” “unrealistic” and “could never happen in America.” Those who rejected my first book Faithless Elector during my wilderness years said pretty much the same things, adding: “no one knows or cares about the Electoral College.” I think they do now.

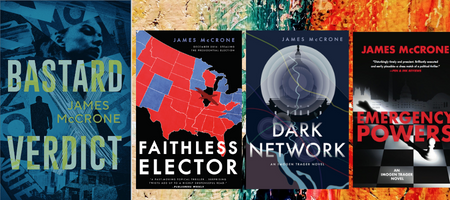

What strikes me as I read about TALK and think about my own works, Faithless Elector and Dark Network, is that the outlines for our current situation have been in place for a long time. It took only an effort of imagination to see where things were going and how it might turn out. I continue to work on the final book in the trilogy and delve into who the conspirators really are and what they want. But as I strive to understand them and write them, I find I have to abandon the current, anguished state of politics as (un)usual once again–this time in favor of a stark, vindictive reality.

This time, reality threatens to outpace imagination. As I challenge and query the plot points and action in the current draft, as I fret over motivations, I worry that my own imagination may not have stretched far enough. Maybe it requires a new perspective.

In TALK, it seems the protagonist Stan Powers is troubled with guilt. In my books the protagonists are propelled by a sense of justice for its own sake, and–in the case of Duncan Calder–as retributive. I worry that such notions may be quickly becoming quaint.

I titled this blog piece “Shakespearian Guilt” because whether we’re familiar with Shakespeare’s villains, we understand the feelings of guilt that accompany heinous acts. Richard III is visited by ghosts of those he murdered, and they curse him: “think on me, despair, and die,” they say. Macbeth is accused by ghosts, Henry IV feels the need to atone for usurping Richard II’s throne. We understand it, and we feel better that these characters are miserable, despite their high status. But what happens when they’re not troubled, when they have no qualms? The epigram for Dark Network hinted at it: “Virtue is more to be feared than vice, because its excesses are not subject to the regulation of conscience” (Adam Smith).

For those who’ve read the books, I see the dark network conspirators as baffled that events have come to this bloody head (a few well placed bribes should have taken care of it); they’re appalled by the body count that’s piling up across the books, but not because there’s blood on their hands, but because it’s untidy, public. Feeling mortified that it has come to this, doesn’t mean they can’t sleep at night, or that quiet moments are troubled with doubt. Far from it. They’re doing the right and virtuous thing; and such men never question themselves or their motives. If they win, it’s because the angels were on their side. If they lose, the forces of darkness have won…but only for now.

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series Faithless Elector and Dark Network. Find them through Indybound.org.

James McCrone is the author of the Imogen Trager political suspense-thriller series Faithless Elector and Dark Network. Find them through Indybound.org.

They are also available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Powell’s Books. Link to REVIEWS

Pingback: Monstrous Imagination | Chosen Words - James McCrone